Project Snapshot

The personal challenge was to develop a rigorous, grounded study and cohesive narrative from a novel, multidisciplinary area of research, facing great risk of over-abstraction and ambiguity. I interviewed civilization game designers, developed novel analysis methods, conducted extensive literature research, and scoured for niche game products.

Navigation: Summary | Initial Concerns | Further Narrowing | Research & Analysis | Products (Results) | Design Experience | Additional Lenses | Lens: Concept Representation | Lens: Systems of Design | Lens: Educational Uses | Lens: Games Research | Lens: Games as Art | Dev Realities: Industry and Indie Games | Dev Realities: Design as a Service | Dev Realities: The Dominion of the Designer | Final Words

Summary

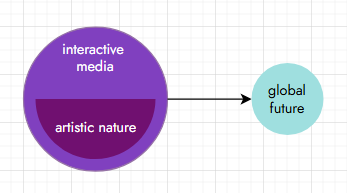

I initially sought out to understand the artistic and aesthetic nature of creating interactive media that encourages thinking about the global future. I focused on the theory, philosophy, and history of artists and designers creating interactive media with global civilization themes.

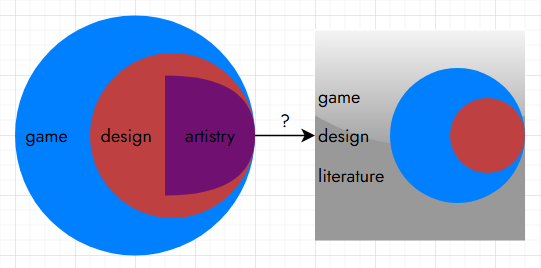

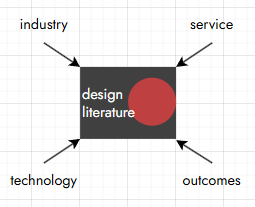

To give the research more shape, I eventually narrowed on artistry in game design and how this was reflected (or not) in published writings on game design, largely represented through game design frameworks and introductory textbooks.

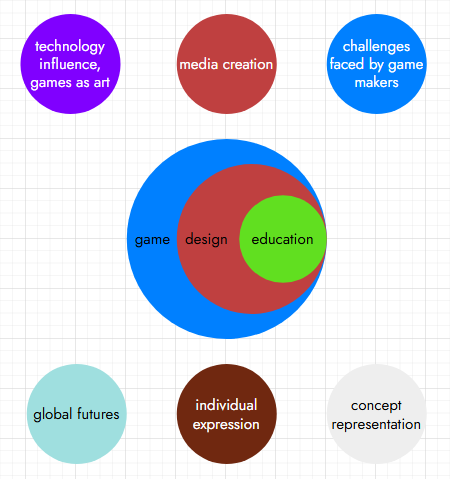

I used the framework and its similarities/differences to other game design literature to explore implications to game design education and game development as well as design and media creation more generally. Other outcomes include methods of concept representation, how designers think about global systems/futures when making a game with such themes (hence civilization games), as well as reflections on individual expression. I also explored definitions of games as art, the influence of technology in art and design, and how these notions relate to challenges game makers face in independent and industry contexts.

I used the outcomes to explore implications to game design education, game development, and media creation more generally. Other outcomes include concept representation as well as reflections on how designers think about global systems and the future when making a game with such themes (hence civilization games). I also explored definitions of games as art, how technology is implicated, and how this relates to the tension between independent games and industry.

Initial Concerns

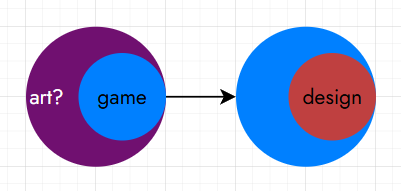

Situated in an art and art ed program, I initially was less focused on games; I was instead focused on the more broader conception of interactive, digital art. I saw games and interactive art as overlapping, with more immersive, open-ended games as a possible subset of interactive digital art.

Thus, in the beginning of my research process, I looked at various interactive and art frameworks such as Locher, Overbeeke, and Wensveen’s aesthetic interaction framework and Leder and Nadal’s revised version of Leder et al.’s aesthetic appreciation and judgments framework. I was fascinated by both interactive digital media and artworks in which user creation was central to the experience.

I was fascinated by both interactive digital media and artworks that included the user in its creation. Motivated by my interests in social systems and cultural narratives, I also found some lineages of futures-thinking to be focused on richly experiential human processes and have similarities to design-thinking; some examples include scenario-building, imagination, utopian thinking, and worldbuilding. I was also curious about how more technical aspects of futures-thinking (forecasting, etc.) came into play.

What was missing was substantive research translating futures-thinking into the creation of interactive digital art. Resultantly, my initial research gap was focusing on bridging the gap between futures and interactive art.

However, the more I needed to substantiate the intellectual foundation of interactive digital art and futures, the more I felt uneasy by the tenuousness of interactive art as a researched field. Much of the research was personal and using very small case studies, which was a bit difficult to form theory around. Artists approached their work with such a wide array of technologies, purposes, and audiences; adding the layer of futures on top made the endeavor even more unwieldy.

After conducting a pilot study, I found the purpose and audience for empirical inquiry to be too nebulous and small under interactive digital art influenced by futures-thinking.

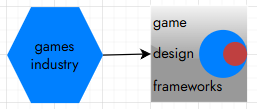

Considering my own previous experiences in game and instructional design, I turned more closely to games. When trying to find substantive research into the crosspollination of interactive digital art and futures, games were often mentioned in anything related to interactive media. The research behind games was more numerous had more studies with structure. For example, one of the more immediate cross understandings of media and futures is social impact games or games for change.

Therefore, I shifted my focus specifically to civilization games and game design education. I approached the research of game design from an art lens.

Further Narrowing

I used the shift to games to highlight different gaps. One contrasting notion between interactive art and games literature is the former's emphasis on experience. Even though game design has been heavily influenced by the art world, the literature translating this was not present.

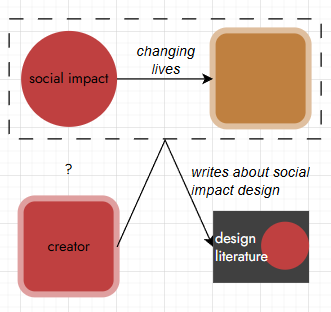

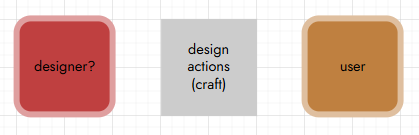

I came to realize that many authors of game design literature (who are mostly designers themselves) have heavily heralded the player or a game’s impact on audiences. This was likely done in part to help establish the validity of the field. Even humanistic designers or designers who have an art background focus on this lens.

As a designer myself, this was ingrained in me to the extent that it was my own blind spot in my research process. It took me some time to more assuredly shift towards focusing on the designer, rather than the player or a game’s impact.

By focusing on the designer and their experience, I was able to pull out a key focus: the designer’s voice, their expressive selves. Yet, seeing that this was largely theoretical from my own perception, and knowing that a lot of designers (in other design fields as well) feel the need not focus on the self and instead on user-centricity, players’ experience, impact, business goals, learning goals, collaboration, etc. I decided to do more investigation.

Simplified primary research question:

In game design, what are the opportunities and limitations towards more artistry?

Additional supporting questions:

How do designers exhibit artistry?

How is aesthetic experience a part of the designer’s experience?

How does artistry inform futures-thinking and vice versa?

How might a fuller understanding of artistry impact game design frameworks?

How might this impact game design education?

Circuitous routes are a bit natural for research. Rather than simply investigating conceptions of games and game design education, I was able to more fully analyze designer’s intent by broadening my research to 1) experience and 2) definitions of art.

I later encourage readers to consider how lessons from this focus could be applied to other contexts, such as media.

Research & Analysis

Methodology

Inspired by the growing inquiry of experimental philosophy, wherein researchers blend philosophical methods with empirical methods, I devised a methodology called grounded ontology, inspired by ontology development, grounded theory, and actor network theory.

To some readers, these words might be jargony because they are! Essentially, I aimed to use empirical data (interview data), existing ontologies (or structures of knowledge, specifically in game design), and theoretical inquiry (developing notions of theory and reliance on literature review) to develop new ontologies. Actor network theory serves as a reminder that the different aspects or “actors” of game design, that is people, processes, technologies, structures, and so forth are all important, and in an attempt to understand game design as a holistic system or “network”, the relationships between these aspects are important as well.

I interviewed 13 designers for around 1-2 hours each. Civilization game designers were chosen as they were likely to approach games in a systems-thinking mindset, paralleling the simulation and holism overlapping with futures-thinking. By looking at creators of games that rely on systems, I was able to investigate human influence in systems, which are often perceived as technical and specific, more akin to information technology or social science.

Analysis

I coded interview data using the constant comparative method, or highlighting key words, phrases, and ideas that were connected to the literature and research questions. The coding was precise and rigorous, with many sentences receiving multiple codes. It needed to be thorough to get an accurate representation of how the population intersected with the many aspects of game design. I used initial themes to guide the analysis then revised and came up with more. I used Nvivo (a qualitative data analysis software) to support my process.

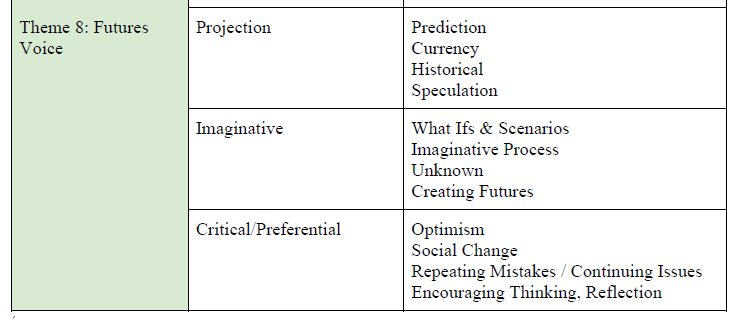

I eventually arrived at 8 global themes, each with sub-themes (organizing themes) which in turn had units (narrower categories).

The 8 global themes were:

1) designer’s general attitudes;

2) designer experience & process;

3) player satisfaction;

4) player cognition;

5) game structure & dynamics (formal elements);

6) dynamics of possibilities in civilization games;

7) representation;

8) futures voice.

Products (Results)

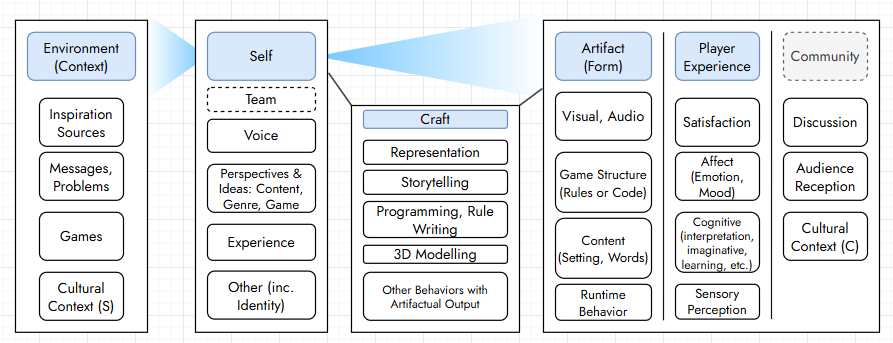

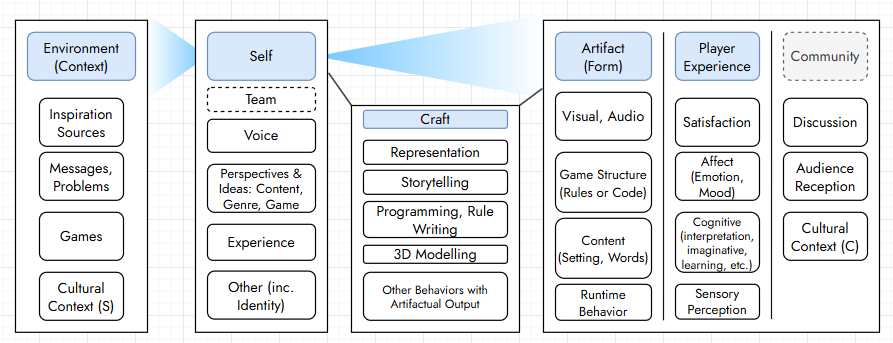

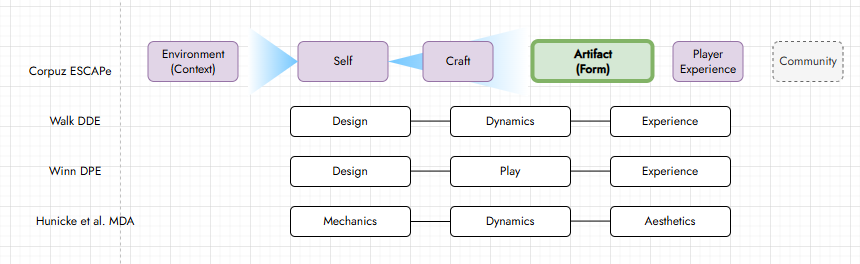

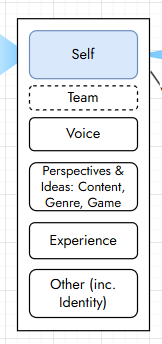

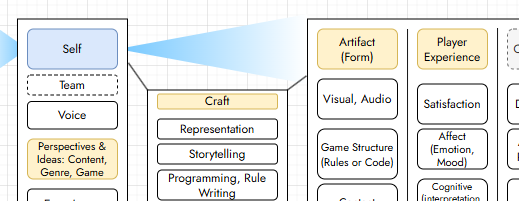

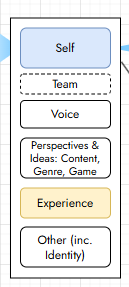

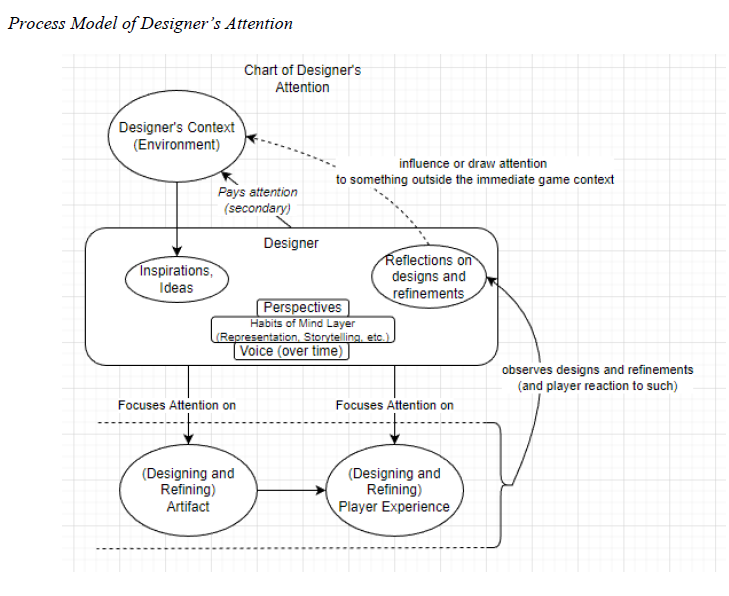

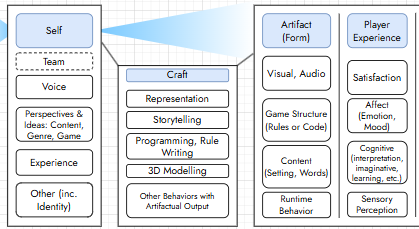

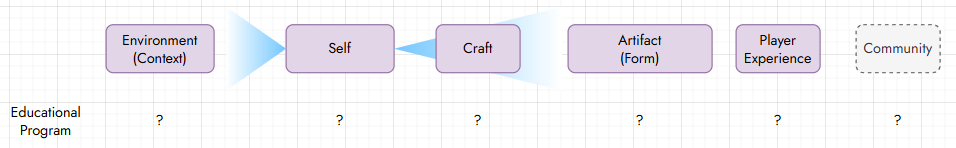

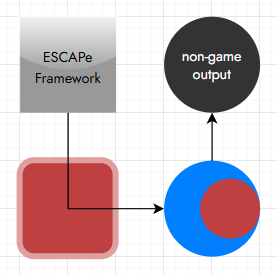

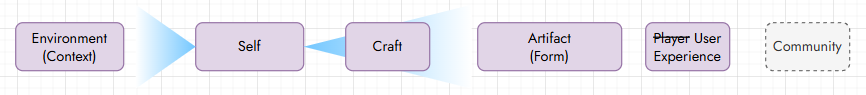

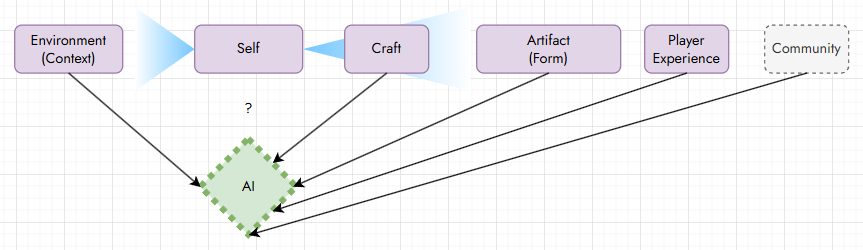

The ESCAPe Framework is the primary result of the research and explicates the many components of game design. The ESCAPe framework explicitly highlights the designer as a central component and distinctly separates the designer from environment, craft, form, and player. The framework also highlights the many relevant aspects of the designer including voice, perspective, and experience.

With the ESCAPe framework, I built upon prior framework research. Prior frameworks include (but are not limited to) Mechanics-Dynamics-Aesthetics (MDA) Framework by Hunicke, Leblanc, and Zubek, Design-Player-Experience by Winn, and Design-Dynamics-Experience (DDE) Framework by Walk. In contrast to prior frameworks, the ESCAPe framework emphasizes the designer in the design system, as influenced by their environment. It also separates craft. It adds further breakdown of player experience in large part inspired by the DDE Framework and Leder & Nadal’s aesthetic experience framework. It also separates the game artifact as form, rather than the artifact being an assumed or inferred aspect encapsulated by the framework.

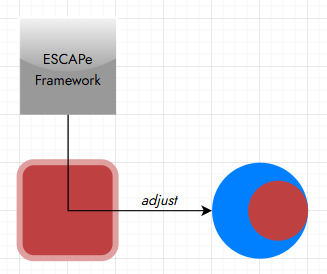

Since the role of the game maker is more explicitly highlighted, I argue the ESCAPe framework could give game makers more clarity and consciousness on how their decisions impact design and how to steer games as a medium more into what they want. Readers can easily notice and give agency to the designer rather than the designer being simply implied.

The framework is most potentially most useful for a designer who is either solo or part of a small team. The designer may want to use games to express or explore certain ideas or perspectives, but lacks clarity on how their notions fit within the larger picture of design and implementation.

For example, let’s say there’s an educational designer who is passionate about using games to teach others about science but is struggling on conveying that passion through the game and to their players. With the framework, the designer can more clearly conceive of their passion and ideas as separate from the considerations of craft, player experience, and form. The designer could then use this framework in tandem with more practical writings (such as Tracy Fullerton’s Game Design Workshop, Jesse Schell’s The Art of Game Design, and Tekinbas and Zimmerman’s Rules of Play) that aid translation of ideas to design.

The framework could also be a useful reminder that the designer’s experience matters, whether for an experienced designer trying to find their voice in the industry or a creative producer attempting to steer their project and all the employees’ voices and potential audiences to a cohesive direction. Impacts on other groups will be discussed below.

I also included other diagrams such as a chart that demonstrates what the study participants’ chose to focus on in part to further articulate how the ESCAPe Framework was derived, and a Civilization Game Design framework which provides a more practical process in creating a civilization game specifically (as derived from the participants), as advice to novice civilization game designers.

Design Experience

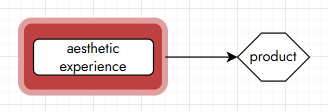

By focusing on the designer’s aesthetic experience through the dissertation, I uncovered aspects important to the designer as it relates to outputting a product.

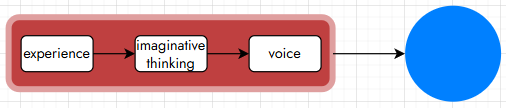

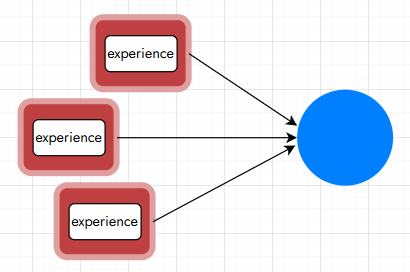

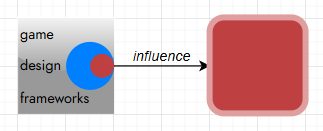

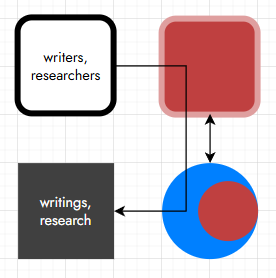

Certain factors from identity to past inspirations to their own struggles vary wildly in importance and presence; however, what’s important is that each designer carries particular aspects of experience with them and these experiences influence their decision-making. In relevance to aesthetic experience, their experience shapes their imaginative thinking which gets translated into their voice which gets put into the game. This is particularly important to note in game design literature which heavily emphasizes the player experience.

By validating the designer’s experience, it becomes easier to consider how a designer is in charge of their output and how it is linked to their perspectives, as discussed earlier. The often emphasized player experience becomes an extension of the designer’s experience, rather than the designer simply being an invisible thinking machine that focuses on delivering an experience for the player. For designers who are attempting to go off the beaten path in game design, designers can use this validation of self and all related components to remind them that their (aesthetic) experience matters.

Through this validation, the designer can analyze, deconstruct, and connect their own experience through the game design process and into the game artifact and player experience. Resultantly, designers can better steer the game development process in their direction.

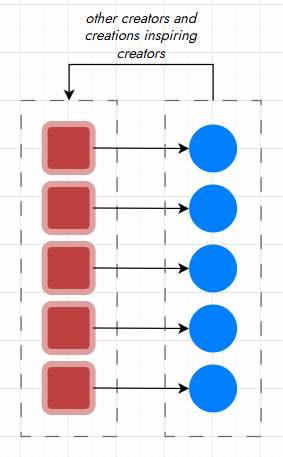

Collaboration becomes a conduit with which all designers share and assert their experience and create something collectively. Thus, designers shaped by different motivations and experiences will produce experiences based on these factors, and a team consisting of members of diverse motivations and experiences will have a wider net to pull from at the risk of a wide variety of ideas without cohesion. For example, someone heavily immersed in pop culture art will be able to bring the visual appeal of popular media, someone inspired by hardware can connect gameplay experiences to the affordances of hardware, and someone with a background in anthropology can embed in the design the richness of culture and possibly consider how the game will proliferate from player-to-player post-release. And so forth.

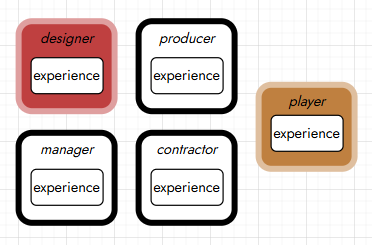

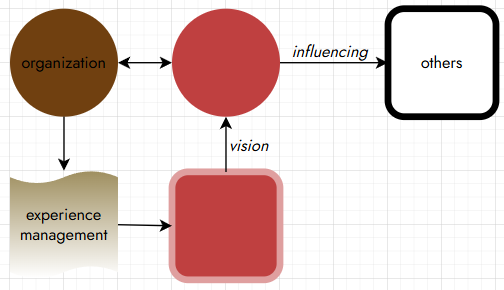

Consideration of designer’s experience also lends to the growing concept of experience management (XM). In organizations, XM is the management of the entire human experience, from organizational employees (with diverse roles) to external vendors/consultants to end users. In theory, an effective design organization uses XM to consider how all aspects of human experience are connected, from experience of design teams’ initial brainstorming, to how managers and producers handle deadlines and conflicting goals, and to how users create community around a final product. Since the ESCAPe framework highlights the designer, the ESCAPe Framework can be the beginning of future research that further explores the ethos behind XM in game design.

Additional Lenses: Concerns and Implications

Through the process of structuring the research, I used supplementary concerns to provide a fuller analysis of the research questions. Additionally, I considered many important implications from the results. These concerns and implications include concept representation, systems, educational uses, games as research, and industry/indie games.

Lens: Concept Representation

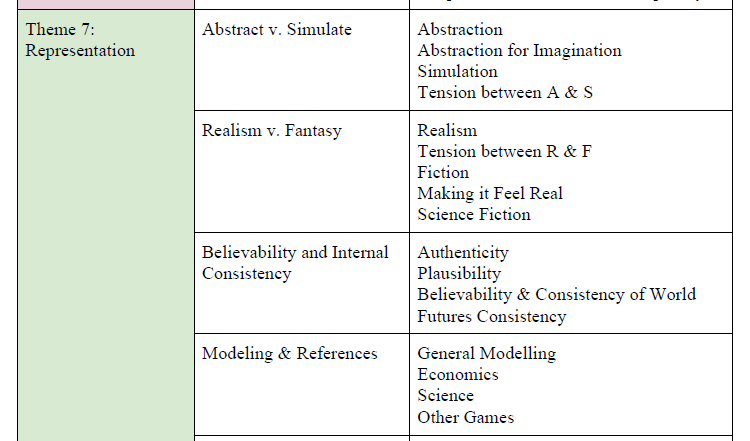

I interpreted multiple different ways designers represent concepts, as captured by theme 7 mentioned above: Abstract vs Simulate, Realism vs Fantasy, Believability and Internal Consistency, Modeling and References.

When designers use their perception to translate game-external concepts into their game, designers use different ways of concept representation; through this research, readers gain insight into this concept translation process and how their beliefs can serve as a guide. Through decisions around concept representation, a designer’s artistry can be expressed. For example, does one choose to make a particular concept more believable to the audience, heralding player experience? And/or do they want to create a more fantastical experience? Designers also use internal dialogues to create and manage large numbers of discrete concepts, which can be a particular difficulty when making civilization games specifically.

As this research focused on a specific style of representation process (representing concepts through structured systems and simulation), researchers could investigate additional processes by which concepts get represented in media. Additionally, creators can use these various modes of concept representation in other media forms.

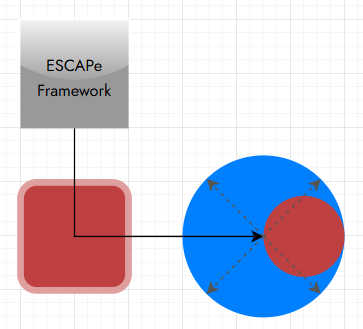

Lens: Systems of Design Complexity and Futures of Possibility

In the dissertation's study, the designers demonstrated how they use systems as a way to convey possibilities for users, who in turn, multiply those possibilities through emergent gameplay. Emergent gameplay is when players create new play experiences, both in ways designers could have intended and ways they could not. Because of the sandbox-like nature of many of these games, the designers expressed how they would intentionally design for players’ serendipity, for players to take what the designers create and do the unexpected. Players would essentially take concepts and form and multiply it into their own. Some designers were more deliberate in this effort than others.

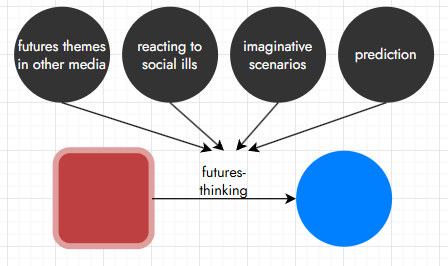

At various degrees, the designers reflected processes that would be expected of futures-thinking; including scenario building, horizon scanning, prediction/speculation, what ifs (alternatives), and preferences (hope).

How and the degree to which the designers cared about futures varied. Some designers were much more activist and humanistic, some were more imaginative and fantastical, some more practical, and others were more interested in replicating future and science fiction themes seen in other games or media, just in their own way or for specific purposes such as for player’s fun.

The act of creating any media (whether making a presentation, analyzing something and writing a paper, or a more artistic endeavor like making music) is often about replicating what has been done or how things have been done but in your own way. Therefore, a designer does not need to think about futures deeply and independently from past media to create a futures-oriented game about civilization, but the capacity to use civilization games for more detailed or rigorous futures thinking is there.

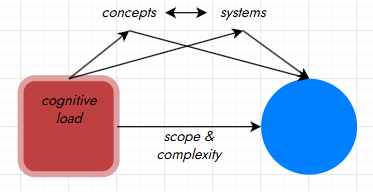

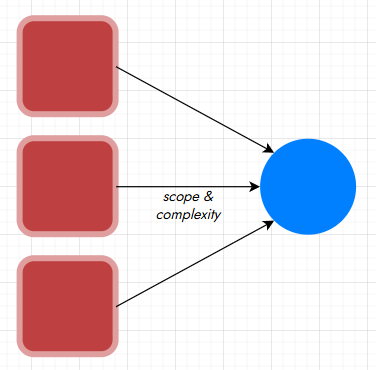

Because civilization game designers create game simulations of potentially very detailed realities, the participants expressed traps of both scope creep and increased cognitive load. Individually and together, the game artifact, the designer’s mental models, and the designer’s perception can exist as complicated networks of connections between concepts, gameplay systems, and so forth. Outside forces such as deadlines and other collaborators act as pressures to repel growing complicatedness in design, but the magnitude and detail of a game is ultimately up to those who create it. Designers can easily dive deeper into endless aspects of information such as the intricate details of a historical culture or the numerous ways different systems of resources intersect; alternatively, they can place self-imposed limits.

While some of the designers reported that diving more into the material sustained their interest, handling the amount of material was not always easy. Just as designers need to be mindful of players’ cognitive load, designers should be mindful of their own. Additionally, the topic matter can be more emotionally intense, such as when dealing with climate change impacts or reading about historical atrocities. Though there is a draw to honor the fullness of all of these realities, ultimately designers are making a game wherein it is not practical nor necessary for all details to appear.

Similar to advice given to any game, smaller developers should consider how to make their game simpler in various ways (and can use the ESCAPe framework to identify and analyze which aspects they would like to be more simple). In this population, solo designers worked on relatively simpler games, whether simpler in thematic detail, thematic reference, mechanics, overall genre, etc. More complex designs can be handled by larger collaborations.

Lens: Educational Uses

The framework is also useful for game design educators looking for ways to structure a game design course or program. Using the whole process lens of the ESCAPe Framework, educators can compare their program to the framework and identify any gaps for their program to cover.

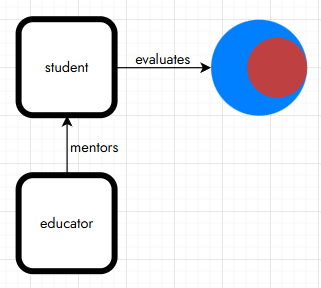

In the classroom, educators can use the ESCAPe Framework to encourage students to evaluate what game design is and imagine what making games can be. Younger audiences may understandably assume the nature of a media form through its common mass perception; for example, thinking of the form of video as big blockbusters, streaming shows, or social media scrolling, rather than thinking of videos used in professional training or video installations in a public space. Students can use the ESCAPe Framework and other game design frameworks to distinctly identify game design’s components, analyze their use, and develop new use cases.

Lens: Games Research and other Applications

Just as students can question the ways in which games are made, experienced professionals can use the ESCAPe framework to adjust their practice. With both the artistic and shifting nature of game development, professionals may find common game design expectations limiting or not sustainable for their own ends.

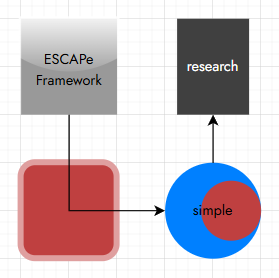

For example, a professional with years of AAA game development looking to move to another industry can use the ESCAPe framework to reflect on their own practice and see the game design process in a new way. If the designer aims to continue to use game design, they can figure out the aspects they would like to focus on or carry into their new career, whether gamifying different fields and practices or making simpler games on their own.

In another example, an under-resourced or incredibly busy academic researcher with some game design experience can use the framework to consider more barebones game design. With such a mindset, the researcher could use game design as a form of research; research is often a solo or small team endeavor undertaken on top of other endeavors. Just as writing has become the default tool in a researcher’s toolkit, other forms such as video, drawing, and potentially game design have their uses and merits. By maintaining their line of inquiry, a researcher can utilize and incorporate the unique aspects of game design, just as another tool or output form in their research process.

Even if no more than a few people shift their design process after actively using the ESCAPe framework as inspiration, the framework serves as a reflection of the different ways game design can grow.

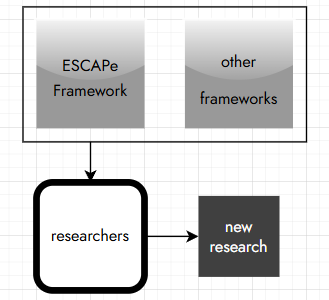

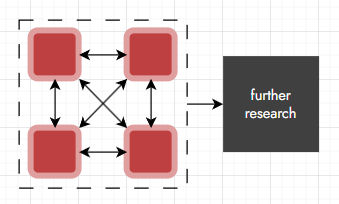

Existing game design frameworks were instrumental in the development of the ESCAPe framework. Personally, I hope more researchers continue to build on game design frameworks.

As models of knowledge and process, frameworks are also prevalent in other fields and I often find there is potential for cross-discipline applicability. For example, the ESCAPe framework can also be applied to other sorts of creation, whether business-driven, impact-driven, or art-driven. For example, a media producer, mobile UI/UX designer, or a social impact artist can consider the same procedural structure of the framework.

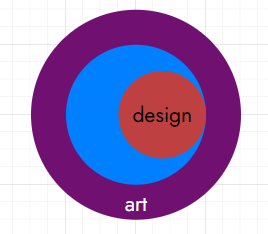

Lens: Games as Art

To justify considering artistry in the development of games and in consideration of the aesthetic nature of the designer’s experience, I explored the question of “what is art?”. A huge portion of the writing on games as art is about games’ status as an art object; I used what has been written about this philosophical question to better contextualize the creative and practical aspects of the design process.

Through my research, I encountered the numerous definitions of art as well as authors’ arguments for why games should or should not be art, its debated status reflecting the open-ended definition of art. Through this open-endedness definition, I used the debate to serve as a reminder that creators can adapt any media form to artistic ends or less artistic ends. Some designers and creatives use games for artistic purposes, art-like endeavors, and/or with artistry-like qualities like self-expression. Games created primarily with artistic intent and games created for other purposes wherein artistic elements are secondary can both be argued to be art.

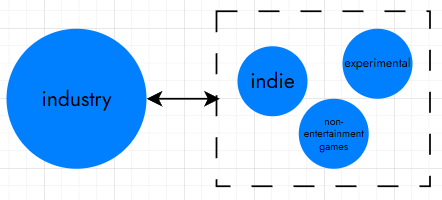

Development Realities: Industry and Indie Games

I also explored the cross-pollination and tension between AAA and indie/solo games as well as games designed for other purposes outside of mass or niche entertainment. This dynamic mirrors similar dynamics between industry and smaller creators in other fields including design more broadly.

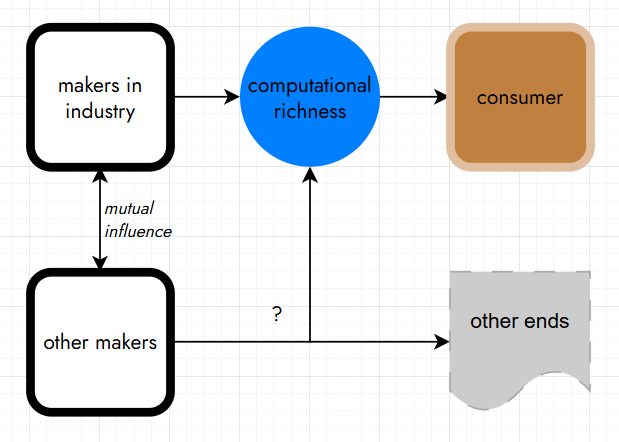

While games have predated digital technology, digital games owe much of their growth to the rise of the television screen and the personal computer. With computer technology comes programming and the power of 1) simulating complex systems, 2) combining media forms to create immersive worlds and experiences (through electronic projection) that have superficially eclipsed traditional media simulacra (text, painting, theater, and more) in their attention and distribution to the masses 3) running increasingly larger and more memory-heavy calculations, all of which are beyond what most humans typically simulate, imagine, and calculate in the everyday. Resultantly, the gaming industry and those it has heavily influenced have capitalized on the power of technology to explode this computational richness and package it to the consumer.

With this deliberate appeal to the consumer through technology advances, the game industry has grown and matured economically. However, this technology-infused maturation did not occur in isolation; niche sectors have continued their development and maturation as well, fueled by other advances such as those in games knowledge and research, social acceptability of games, and accessibility of design tools and methodologies. These sectors include indie games, board games, games as art, games for social impact, serious games, educational games, and creative technology use in other media.

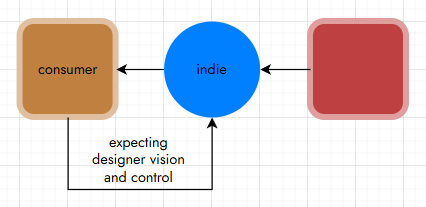

Indie game makers have developed a market niche for those interested in more expressive uses of games, or at least games through which the target consumer has more expectation of designer vision and control.

Similarly, board game makers — many of whom are solo or independent — have fueled a recent renaissance in the diversity and sophistication of board game design. With crowdfunding avenues and the use of board games in game design education, the potential for smaller teams to be innovative and create commercial appeal has been repeatedly realized.

Makers of art games or other creative/interactive technology have continued to shape and play around with definitions of art and game. Their efforts are appreciated by those looking to experiment with what is possible with design and technology interactivity.

It is apparent that there are markets, pathways, and interests in independent, solo, and experimental making. By simply making games in non-usual manners and for non-usual purposes, the field of game design has expanded. Game makers can be more flexible with what games are, be in charge of them, and better use games in flexible manners just like other media forms to support any goal they may have.

I draw these sector comparisons to emphasize that existing framework literature serves more industry notions of design than it does independent and solo. As a reminder, in my study both industry and independent designers exhibited artistry.

Development Realities: Design as a Service

Those who have made games that would fall under loose groupings such as games for change, games for social impact, and serious games have also opened up possibilities for looking at games differently. However, it should be noted that fields like serious games and games for social impact in some ways act parallel to industry rather than causing friction. There often is an assumption that these two ends are vastly different; in my view, this is simply a shifting of ends rather than a shifting of the entire attitude or process. Unlike games as art (which for a while used to be considered a part of serious games), serious games and games for social impact focus on player outcomes, not much different than industry.

Referring to design more broadly, design for social impact is rooted in design as a service. In the effort to integrate with industry’s inherent focus on appealing to the customer for financial prosperity, many designers (many of whom come from humanities and arts backgrounds) have ensured design has a financially verifiable purpose by focusing on design’s impact on outcomes.

Through this emphasis and proliferation of service, such designers seeking to broaden the context of design have translated industry service into social impact service. Social impact designers have strengthened the validity of design and design-thinking by transforming the lives of millions throughout the world through enhanced products and experiences. However, just like creating design for business purposes, the central focus of design as social impact is on the outcome of the target market, rather than the expressive power of design for the creator. A focus on measurable outcomes begs designers and organizations to wonder how they can create better outcomes in every iteration of a product or experience.

Designers who have built careers focusing on social impact, design as a service by offering engaging (player) experiences, technology growth, or organizational prosperity have sustained and created much innovation in design more broadly and game design more specifically. These designers have contributed immensely to a professionally, economically, and intellectually viable design field ecosystem. They have also translated their work into design literature.

Development Realities: The Dominion of the Designer

However, design as a field is limited when design literature over-reflects reliance on outcomes. While there is plenty of writing on designers’ lives, histories, and perspectives and how it influenced their work, when it comes to design frameworks, the visibility of the designer is too often absent. Design frameworks are the conceptual tool used to assist the designer, reminding them of steps or key elements in completing design.

As reflected in my research (which focused on game design), an over-reliance on outcomes has led to knowledge creation, design language, and to a certain degree design ethos that has privileged what industry has prioritized: the technical aspects: technology, programming, information systems, collaborative effort, design tools, and so forth… and servicing user/customer experience aspects: engagement, immersion, excitement, attention… fun in games. By prioritizing technical knowledge and customer experience, design becomes intertwined with the power of technology and a service.

All this in turn shows how game design frameworks — inclusive of the ESCAPe Framework — have come to be, as reflections of common ways of doing things in both design more broadly and game design specifically, influenced most heavily by industry… with secondary avenues in the supportive background. As a largely applied field, game design textbooks and the frameworks which scatter game design literature more generally have relied on practical language often relying on industry with potential for other ways to make their mark.

There is room for the designer to be more explicitly called out and be integrated as critical in the design process, even when the process needs to be heavily outcome-oriented. This is of particular importance because current and future designers at least partially rely on design literature to grow and shift their design practice. The popularity and viability of alternative methods of game development is growing, as is the ease of integration of game design and gamified elements into other fields (just like how other media forms such as video have been integrated). Additionally, the gig and content generation economy is expanding, reflecting how entrepreneurial individuals seek to use their skills, advertise their services, and have a more complete sense of their own place and motivation. Thus, the need for an explicit designer role is all the more apparent.

This is key in the proliferation of AI wherein it is easier for the AI to replicate a design because it can simply replicate a framework which has been de-humanized outside of the user/player to whom it attempts to appeal. Unless fed particular data, AI does not know exactly who individual people are; with the designer as part of the framework, AI can only speculate and create a fake persona based on external factors. Without the designer, AI has an easier time mimicking design process simulacra.

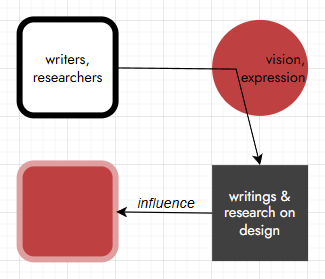

Thus, there need to be enough writers and researchers in design and game design who contribute to investigating the expressive power of the designer and how it can be central to design. Through more deliberate efforts to highlight the designer in game design literature, the designer can be a recognized, proactive, agent in the design process, one that can be described and further researched.

By further investigating the designer, researchers (such as myself) help game design become more recognized as more than just a service to the player or a creative business opportunity — game design becomes more inclusive of designer vision and expression. Of course, this isn’t to say that (successful) game designers and producers have not already been exercising their vision and expression as my research shows, but rather the fields’ researchers and practitioners should not allow these literature gaps to remain as it leaves space for learner confusion and prohibits the possible growth of visible opportunities to designers who are more interested in using vision and expression.

To note, most of the designers in bigger organizations in my study demonstrated a creative agency, even if some of the creative decision making is subsumed to other positions. Those in solo or smaller teams appeared to express greater creative control over their whole product, which raises unique questions about expression amidst large team collaboration. Further research could expound on collaboration and how people share and shift their perspective in a group.

Final Words

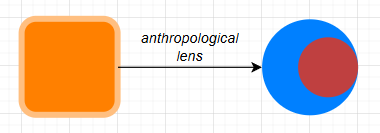

I personally found it beautiful to look at civ game design and game design more broadly as an anthropological practice. I also enjoyed considering how my research is indicative of design trends at large and the dynamics among society, technology, industry, and makers.

Whether people choose to focus on programming, rules, art, mechanics, personal expression, ideas, innovating hardware, creating immersion, games for education, games for social impact, player fun, etc., there are many ways or strains of making civ games and games more broadly. Looking within these strains, researchers and practitioners can explore many processes that are valid not only because some humans choose to engage with games in such ways, but also simply because the ability to make games in that way exists.

With a greater focus on experience management, organizations can better heed the interests of creatives such as designers. In turn, more designers and those interested in design can find the collateral to develop their own vision and integrate it into existing design manners at an organization as well as innovate new opportunities, altering others’ expectations of the capabilities of design.

The full dissertation is available on ProQuest. If you only have a 23-page preview access on ProQuest, reach out to me for a full copy.